Top Factors That Drive Inflation and Price Increases

Inflation is like a mysterious force. We feel its impact—prices go up, and our money doesn’t buy as much—but many people don’t really know what causes it or how to control it. That’s because inflation works at the macroeconomic level, which involves complex and interconnected factors.

- Demand-pull inflation happens when the demand for goods and services is greater than what the economy can supply. This often occurs during strong economic growth, when people have more income, interest rates are low, loans are easy to get, and consumers and investors feel optimistic.

- A real-life example: In 2021–2022, after the COVID-19 pandemic started to ease, many countries experienced demand-pull inflation. People began spending heavily after holding back during the pandemic. Demand surged, but supply hadn’t fully recovered, so prices went up.

- Cost-push inflation happens when the cost of producing goods and services increases. To protect their profits, producers raise prices. A clear example of this was the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, which caused energy and wheat prices to spike, since both countries are major exporters. As a result, many nations faced cost-push inflation.

In the past, classical economic theory said that if the amount of money in circulation increases, prices will rise too—because more money is chasing the same amount of goods. This idea is known as the quantity theory of money.

However, the U.S. Federal Reserve now believes that this relationship isn’t as strong as it used to be. Why? Because money can be saved or invested instead of spent immediately. Also, technology, globalization, and production efficiency help keep prices down. Inflation is also influenced by public expectations and government policies.

That’s why we need to look at inflation more deeply—not just as “rising prices,” but as the result of complex economic forces. By understanding its main causes—especially demand-pull and cost-push inflation—people can better analyze the economy and evaluate government policies.

Demand-Pull Inflation

Demand-pull inflation is a type of inflation caused by a rise in overall demand for goods and services (called aggregate demand) that exceeds a country’s ability to produce them (known as aggregate supply).

Here’s a simple analogy:

Imagine you normally sell 100 cupcakes a day. Suddenly, 150 people want to buy them. Since you can’t make more cupcakes right away, you raise your prices because you know people will still buy them. If all cupcake sellers do the same, prices in general go up—that’s inflation.

So why does demand exceed supply? There are a few reasons:

- The economy is growing. When things are going well, more people get jobs or pay raises, and they feel confident spending more money.

- Production can’t keep up. Companies may not be able to increase output quickly due to limited time to build new factories, not enough workers, or a shortage of raw materials.

A real-world example:

In 2021, the auto industry faced a global shortage of semiconductor chips. Demand for cars was high, but production was slowed down. As a result, car prices jumped significantly.

When people expect prices to keep rising, they tend to buy now rather than later. They save less and spend more quickly, which pushes demand even higher.

To manage these expectations, the U.S. Federal Reserve (The Fed) sets an inflation target to help guide public confidence. Their goal is to keep core inflation at around 2% per year.

Factors of Demand-Pull

Here’s a deeper explanation of the main factors that can cause demand-pull inflation, along with real-life examples:

Marketing and New Technology

Demand-pull inflation doesn’t always spread across all sectors right away. Sometimes, it starts in specific areas—especially high-value products or assets—and then spreads to other sectors through a chain reaction.

Big companies can also create demand strategically, not just based on consumer needs, but by shaping how people perceive value or quality.

Take Apple, for example. The company uses strong branding and exclusive designs to make its products feel like “must-have” items.

Because demand is so high, Apple can charge higher prices—often much more than competitors. Even though the production costs may be similar, customers are willing to pay more because of brand loyalty and the prestige of owning Apple products.

This drives up prices in the premium tech segment and sometimes pushes competitors to raise their prices too, contributing to inflation in that market.

Inflation isn’t limited to consumer goods or tech products. Assets like real estate and stocks can also experience inflation—and sometimes even faster.

A real-world example:

In the early 2000s, financial institutions created new products like mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and real estate derivatives. These innovations made it easier for banks to give out home loans—even to people with poor credit (known as subprime mortgages).

This easy access to financing led to a huge jump in housing demand—not because people truly needed more homes, but because it became so easy to borrow money. As a result, home prices skyrocketed, and a housing bubble formed.

Expansionary Fiscal Policy

Money supply refers to the total amount of cash and bank deposits held by people and institutions. When the money supply increases sharply, people have more purchasing power. This boosts demand for goods and services. But producers may not be able to immediately match the increased demand—so prices go up.

When there’s too much money circulating, the value of the local currency often weakens compared to foreign currencies. For example, if the U.S. dollar loses value, imported goods become more expensive. This includes electronics, cars, and raw materials used in production. As the cost of imports rises, so does the cost of producing goods domestically, leading to wider inflation across sectors.

Let’s say the U.S. prints too much money. The dollar may weaken against the euro or yuan. As a result, imported items get pricier. Manufacturers, facing higher costs, raise their prices—and inflation spreads throughout the economy.

One major cause of this is expansionary fiscal policy, where the government tries to stimulate economic growth by increasing public spending, cutting taxes, or sending direct cash assistance (stimulus payments) to citizens. All of these actions boost the money supply.

A real-world example:

During COVID-19 (2020–2021), many countries injected trillions of dollars into their economies through stimulus packages. In the U.S., people received direct payments into their bank accounts to help maintain spending power during the crisis.

But once lockdowns eased, people began spending heavily—yet global supply chains were still disrupted. This mismatch caused a major spike in prices.

Most economists agree that these large-scale stimulus efforts were one of the key drivers of the high demand-driven inflation that followed.

Expansionary Monetary Policy

Expansionary monetary policy is a strategy used by a central bank—like the Federal Reserve (The Fed)—to increase the money supply in the economy. The main goal is to stimulate economic growth, especially during a slowdown or recession.

One of the key tools of this policy is lowering the benchmark interest rate. The federal funds rate is the interest rate banks charge each other for short-term loans. When the Fed lowers this rate, it becomes cheaper for banks to borrow money from one another. In turn, banks can offer lower interest rates on loans to businesses and individuals.

This encourages people to borrow and spend more, boosting demand. But if the money supply grows too much—while the amount of goods and services stays the same—there’s an imbalance. Demand rises, but supply doesn’t. As a result, prices go up and inflation happens.

Still, printing more money or lowering interest rates doesn’t always cause inflation. Inflation can also be triggered by other factors. Monetary policy alone isn’t always the direct cause.

Most of the time, inflation results from a combination of demand-pull and cost-push factors.

A great comparison is between the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic:

- In 2008, the Fed used expansionary policy to fight the recession. But inflation stayed low because overall demand was weak—people weren’t spending much.

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, governments and the Fed also used expansionary policies, including stimulus checks and low interest rates. But this time, inflation surged.

Why? Because in addition to high demand (demand-pull inflation), there were also supply-side issues—like disrupted supply chains and higher production costs—which created cost-push inflation. The combination caused prices to rise sharply.

Cost-Push Inflation

The second main cause of inflation is called cost-push inflation. This happens when the cost of production rises, and companies pass those higher costs on to consumers in the form of higher prices. This can occur even if demand stays the same—it’s not driven by people wanting to buy more.

Here are some key causes of cost-push inflation:

Global Supply Chain Disruptions

- When the flow of goods is disrupted—due to lockdowns, container shortages, or port congestion—products become harder to get. This drives up logistics and production costs, which then leads to higher prices.

- Example: During the COVID-19 pandemic, supply chain issues caused price spikes in everything from electronics to groceries.

Monopolies

- A monopoly is when one company controls an entire supply of a product or service. With no competition, the company can raise prices freely. That’s why the U.S. created the Sherman Anti-Trust Act (1890)—a law designed to prevent companies from dominating markets and causing inflation through price control.

Natural Disasters

- Events like hurricanes, earthquakes, or floods can damage factories or infrastructure. When production drops, supply shrinks, and prices rise—even if demand hasn’t changed.

- Example: After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, many oil refineries in the Gulf of Mexico were damaged. This caused fuel supply issues and a sharp increase in gas prices.

Declining Natural Resources

- As natural resources become harder to find or extract, the cost of obtaining them goes up. This forces producers to raise prices to maintain profits.

- For example, if mining certain metals becomes more expensive due to scarcity, electronics or cars that use those metals may also become more expensive.

Conclusion

Cost-push inflation is a type of inflation caused by rising costs on the supply and production side, not by increased consumer demand. It can be triggered by global supply chain disruptions, market monopolies, natural disasters, and scarcity of natural resources.

In the real world, understanding these causes is crucial. It helps governments and policymakers create more targeted and effective economic strategies to manage inflation and protect consumer purchasing power.

Acne

Acne Anti-Aging

Anti-Aging Business

Business Digital Marketing

Digital Marketing Economics

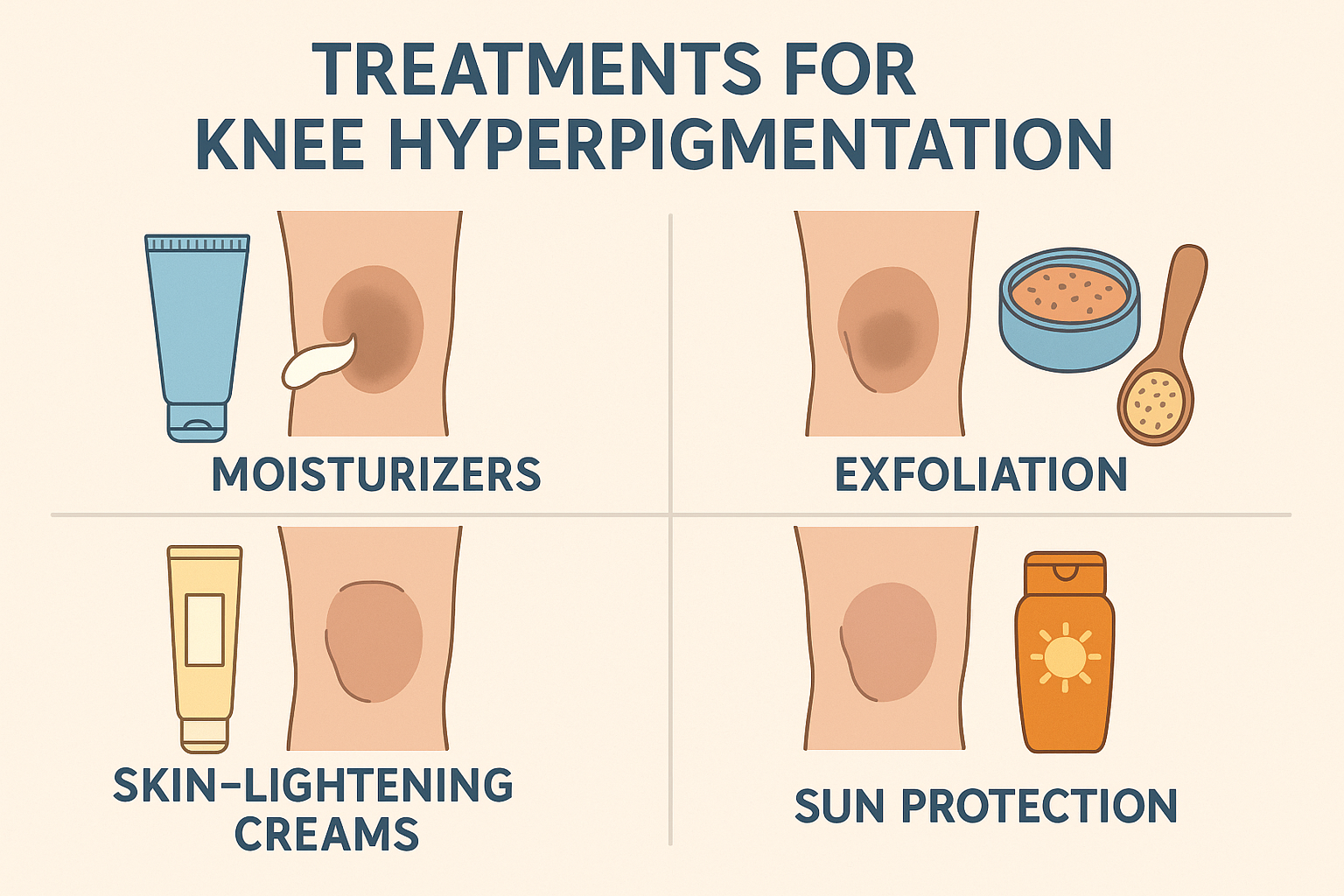

Economics Exfoliation

Exfoliation Hair Removal

Hair Removal Movies

Movies Personal Finance

Personal Finance Websites

Websites